Watching the film, there were a number of really interesting scenes to discuss, but that last scene stood out. We have all seen movies and shows that revolve around war. When the war is over and the soldiers get to return home, we see the celebration of victory and the reunion of families. That is how I would expect a movie like this to end. For me, the Soviet twist here is when Veronica hands starts handing out the flowers to strangers. It is as if Stepan’s speech and her experiences throughout the movie have almost helped her see that the flowers belong to everyone. Everyone in the Soviet Union played a role in the war effort. It really is great branding for the Soviet government. At the same time, we see how memories of war can destroy lives. What are your thoughts on the final scene? Is there anything to say about Stepan’s speech advocating for peace? Again, after the harsh experiences of war, of course you might want to try to avoid another one, but that is probably not realistic.

Diary of Podlubnyi

As we have frequently encountered throughout the semester, the Soviet government under Stalin was really only concerned with achieving its own internal goals, no matter the cost. The best way Stalin and his government saw to do this is embodied in a quote from today’s reading: “Only the state could imbue him with the notion of being a free agent. It was through the Soviet state that Podlubnyi acquired a sense of purpose, indeed the norms to define and guide his personal life.s his case makes clear, Soviet man could realize himself only by working for the state” (89-90). This is not new and there are similar references throughout the reading. Think about how it would feel in the moment if you were there. What are the negatives associated with policies like this? Is damage done to the culture of the nation as a whole? If the nation becomes successful and powerful, does that justify the actions of the government?

Rare Symbol of Success

Reading the piece from Pasha Angelina, it is clear that she approves of Stalin’s efforts in the country side. At one point she says, “It was with my heart rather than my mind that I had apprehended the grandeur of what Stalin and the party were doing in the countryside” (307). This is all happening to Angelina while thousands of other people are struggling to survive under these same policies. What do we make of that, and how do we reconcile this with the fact that collectivization as a whole killed millions? Why do you think Angelina was able to be successful, and how many people could have actually been just as successful? Finally, we know that the Soviet Government carefully controlled the flow of information into, out of and throughout its nation. Does that change our perception of her story?

What Went Wrong

In the introduction to the chapter we read from Marianne Kamp, she says “The Hujum as originally envisioned focused on enforcing laws thatgave women equality, creating literacy programs and bringing womeninto the labor force. Communists in Central Asia and the Caucasus were supposed to attack every obstacle to women’s equality” (150). On paper, these few sentences alone do not all that bad, but that is where my question comes in. Having read about the experiences of people who lived during the time, it is clear that the policy was flawed. What are some things the Soviet government may not have considered when it implemented these policies?

Crafting Public Perception

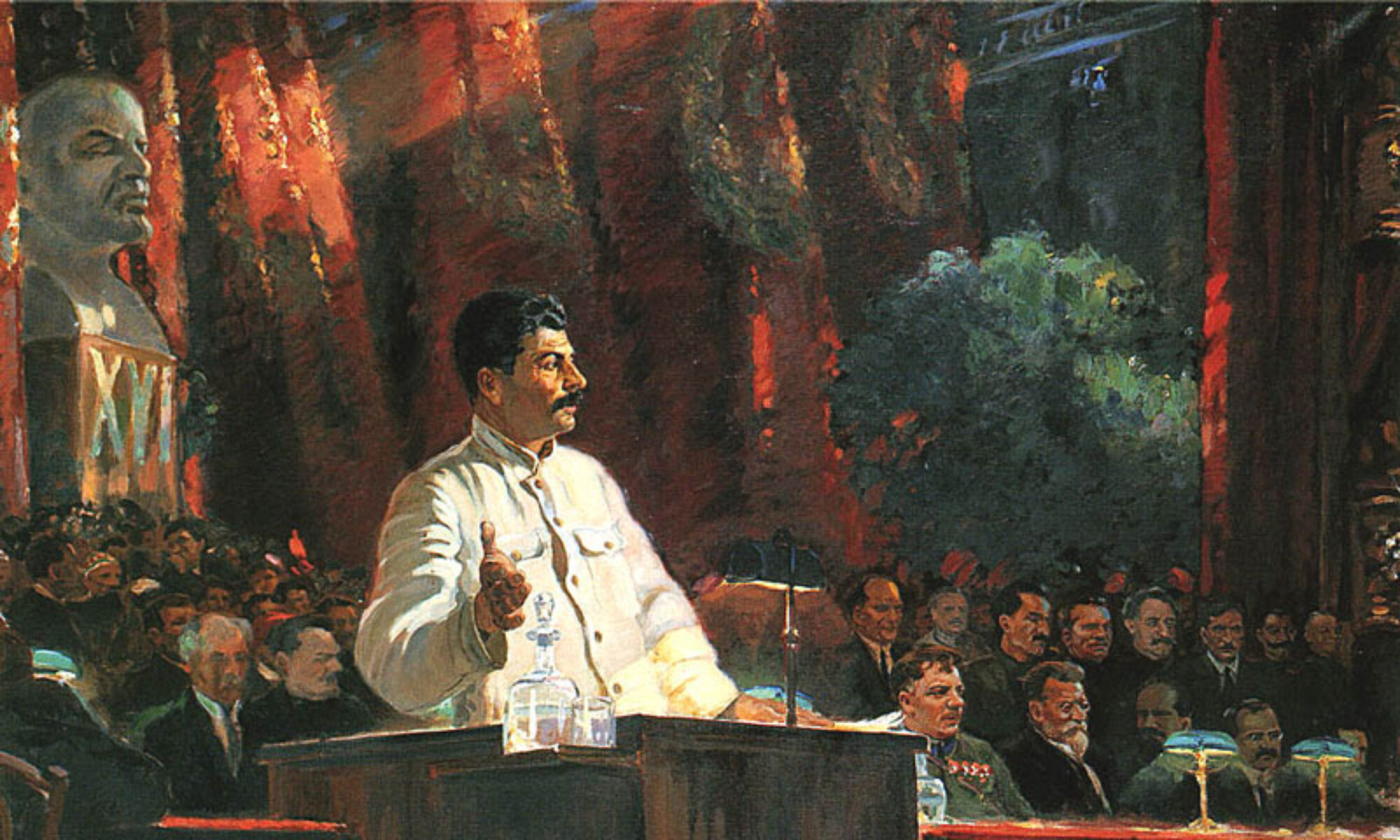

Since Syd and I are leading class tomorrow, I wanted to bring up a point to discuss to get us started in thinking about the use of visual images like the ones we see in the slideshow to craft the public’s perception of a government official. For someone like Stalin who was the single most powerful person in the Soviet government, how important is it to plan and execute a campaign to shape the public’s perception? Should images work to promote both the ruler and their initiatives at the same time, or is it more important to simply achieve policy goals?

“Every revolution needs its heroes.”

It is really fascinating how the Bolsheviks went from having literally no experience with propaganda to mastering it so quickly. They created a dynamic machine that could make material to support just about any campaign or goal. I think we should spend some time talking about propaganda we have in our own culture and how that effects us, if at all. Is it something we notice? For the Soviets, do you think people knew the government was essentially manipulating them, or were they blind to the government’s true intentions?

What is Soviet music?

In Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia, we read all about the Resolution of 1932 and the way that enabled the Party to take the primary role in determining the direction that Soviet composers would take when creating new music. This had a profound impact on the music being produced. Schwartz says, “advanced composers became commonplace. Young composers endeavoured to be inoffensive, and conservatism became a cherished virtue, while musical nationalism experienced a revival” (115). The Party’s desire to become more involved in music indicates that they felt it was an important aspect of Soviet society that deserved their attention. That leads me to my questions: Why was music so important to Soviet culture? Additionally, the quote I included mentions “musical nationalism.” What is that and why is it significant?

Circus

Just like the last film we viewed, Circus (1936) is certainly a strong piece of Soviet propaganda, but it takes a different direction. As time went on and the Soviet government increased its level of focus on spreading its ideology around the world. This depiction of an accepting society ready to embrace just about anyone, unlike America, is probably a good message to send. That is where my question comes into play. Why does the Soviet government need to send this message to the average citizen? The government tightly controlled the flow of information to its people. If it wanted people to know about how terrible America was, they could have easily (and did) fabricate news and events happening around the world. It seems to me that this movie was made more for an audience outside of the Union. Another interesting question I have been thinking about is whether or not the film makes a valid point. In 1936, a film like this released in America would probably have spelled the end of the line for the studio and actors who made the film. At the same time, the Soviet Union was not nearly as accepting as the depiction at the end of the movie.

Is the argument effective?

There were a few things in this part of story that stood out to me. On page 472, when Pavel reaches out to the Party, I started thinking about how effective that was. It is like a built in advertisement, much like the whole book. It got me to thinking about how effective that actually might have been. If you read a book that told you the government here in the United States would always be there to help you, would you believe it? Would reading that have any effect on your opinion?

The end to Pavel’s story also stuck out to me as something to be discussed. Through all of his struggles and issues, he still ends up finding a way to be productive to Soviet society by writing his novel. As readers of the present day in a completely different country, our perception of the novel is certainly different than the Soviet citizens who read it. Trying to think of what it might be like to read this during that time under Soviet rule, it seems like it could have an inspirational effect. Anything is possible with hard work and determination. So I’ll ask the same question as I did above, would this work on you if it was story written here in the United States trying to convince you to change your perception of something?

Zhdanov’s Speech

In studying Soviet history, I often find that primary sources are my favorite way to really understand what is happening. Andrei Zhdanov’s speech to the first Congress of Soviet Writers contains a few points that I think would be worth discussing. The overall tone of the speech closely follows the format often employed by Stalin: make claims about some major “achievements,” and follow it up with some “minor” adjustments to make things even better. One claim that “Only Soviet literature, which is of one flesh and blood with socialist construction, could become, and has indeed become, such a literature-so rich in ideas, so advanced and revolutionary” stands out to me. This is something that Zhdanov really leans on as a core objective. He recognizes how powerful literature can be in a propagandist’s tool box. What does it mean for the “flesh and blood” of literature (and other arts) to be constructed in a socialist way? Is it ok to include portions of the Soviet Union’s not so socialist past during the Imperial era?